The census fails to account for taxes and most welfare payments, painting a distorted picture.

By Phil Gramm and John F. Early

Nov. 3, 2019 3:43 pm ET

Never in American history has the debate over income inequality so dominated the public square, with Democratic presidential candidates and congressional leaders calling for massive tax increases and federal expenditures to redistribute the nation’s income. Unfortunately, official measures of income inequality, the numbers being debated, are profoundly distorted by what the Census Bureau chooses to count as household income.

The published census data for 2017 portray the top quintile of households as having almost 17 times as much income as the bottom quintile. But this picture is false. The measure fails to account for the one-third of all household income paid in federal, state and local taxes. Since households in the top income quintile pay almost two-thirds of all taxes, ignoring the earned income lost to taxes substantially overstates inequality.

The Census Bureau also fails to count $1.9 trillion in annual public transfer payments to American households. The bureau ignores transfer payments from some 95 federal programs such as Medicare, Medicaid and food stamps, which make up more than 40% of federal spending, along with dozens of state and local programs. Government transfers provide 89% of all resources available to the bottom income quintile of households and more than half of the total resources available to the second quintile.

In all, leaving out taxes and most transfers overstates inequality by more than 300%, as measured by the ratio of the top quintile’s income to the bottom quintile’s. More than 80% of all taxes are paid by the top two quintiles, and more than 70% of all government transfer payments go to the bottom two quintiles.

America’s system of data collection is among the most sophisticated in the world, but the Census Bureau’s decision not to count taxes as lost income and transfers as gained income grossly distorts its measure of the income distribution. As a result, the raging national debate over income inequality, the outcome of which could alter the foundations of our economic and political system, is based on faulty information.

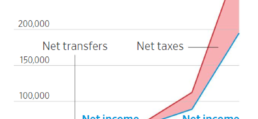

The average bottom-quintile household earns only $4,908, while the average top-quintile one earns $295,904, or 60 times as much. But using official government data sources on taxes and all transfer payments to compute net income produces the more complete comparison displayed in the nearby chart.

The average bottom-quintile household receives $45,389 in government transfers. Private transfers from charitable and family sources provide another $3,313. The average household in the bottom quintile pays $2,709 in taxes, mostly sales, property and excise taxes. The net result is that the average household in the bottom quintile has $50,901 of available resources.

Government transfers go mostly to low-income households. The average bottom-quintile household and the average second-quintile household receive government transfers of some $17 and $4 respectively for every dollar of taxes they pay. The average middle-income household receives $17,850 in government transfers and pays an almost identical $17,737 in taxes, while the fourth and top quintiles of households receive government transfers of only 29 cents and 6 cents respectively for every dollar paid in taxes. (In the chart, transfers received minus taxes paid are shown as net government transfers for low-income households and net taxes for high income households.)

The average top-quintile household pays on average $109,125 in taxes and is left, after taxes and transfer payments, with only 3.8 times as much as the bottom quintile: $194,906 compared with $50,901. No matter how much income you think government in a free society should redistribute, it is much harder to argue that the bottom quintile is getting too little or the top quintile is getting too much when the ratio of net resources available to them is 3.8 to 1 rather than 60 to 1 (the ratio of what they earn) or the Census number of 17 to 1 (which excludes taxes and most transfers).

Today government redistributes sufficient resources to elevate the average household in the bottom quintile to a net income, after transfers and taxes, of $50,901—well within the range of American middle-class earnings. The average household in the second quintile is only slightly better off than the average bottom-quintile household. The average second-quintile household receives only 9.4% more, even though it earns more than six times as much income, it has more than twice the proportion of its prime working-age individuals employed, and they work twice as many hours a week on average. The average middle-income household is only 32% better off than the average bottom-quintile households despite earning more than 13 times as much, having 2.5 times as many of prime working-age individuals employed and working more than twice as many hours a week.

Antipoverty spending in the past 50 years has not only raised most of the households in the bottom quintile of earners into the middle class, but has also induced many low-income earners to stop working. In 1967, when funding for the War on Poverty started to flow, almost 70% of prime working-age adults in bottom-quintile households were employed. Over the next 50 years, that share fell to 36%. The second quintile, which historically had the highest labor-force participation rate among prime work-age adults, saw its labor-force participation rate fall from 90% to 85%, while the top three income quintiles all increased their work effort.

Any debate about further redistribution of income needs to be tethered to these facts. America already redistributes enough income to compress the income difference between the top and bottom quintiles from 60 to 1 in earned income down to 3.8 to 1 in income received. If 3.8 to 1 is too large an income differential, those who favor more redistribution need to explain to the bottom 60% of income-earning households why they should keep working when they could get almost as much from riding in the wagon as they get now from pulling it.

Mr. Gramm is a former chairman of the Senate Banking Committee. Mr. Early served twice as assistant commissioner at the Bureau of Labor Statistics.