Disposable real per capita income rose 5.5% in 2020, the highest rate since 1984, due largely to transfer payments.

By Phil Gramm and Mike Solon

Feb. 2, 2021 6:17 pm ET

Even among economists who strongly support President Biden, a consensus is growing that the economy emerged from last year set for a robust recovery. That view has been espoused by Bill Clinton’s Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers and Barack Obama’s former top economist Jason Furman. Both have expressed concern that the economy may overheat.

The most encouraging sign that recovery will be strong as the vaccines take hold is not that real gross domestic product rose 7.5% in the third quarter, offsetting 83% of the economic collapse produced by the shutdown in the preceding quarter. Nor is it that 16 million of the 22 million jobs lost have been restored. The most encouraging sign is how much the total purchasing power of American families has expanded during the crisis, reaching record highs.

To be sure, many Americans have taken a serious hit: Commerce Department data show total employee compensation in the second and third quarters of 2020 was down by $215 billion compared with the first quarter. Yet government personal transfers were up $893 billion—four times the compensation lost. In the second quarter alone, real per capita disposable income was up 10.5% compared with the first quarter—25 times as fast as the average quarterly income growth in the prior two years.

This surge in personal income was driven by government stimulus equal to $2.6 trillion, more than all the private wages and salaries paid in the first quarter of 2020. While preliminary fourth-quarter figures show that personal income declined from the previous quarter, real per capita disposable income in 2020 grew 5.5%—the highest growth rate since 1984, the peak of the Reagan recovery. All of this occurred before the $900 billion December stimulus took effect.

So what happened to all that money? As transfer payments surged in the second quarter and the shutdown curtailed personal-consumption expenditures, pent-up purchasing power spiked. Quarterly savings rose by almost $800 billion. The historical savings rate of 7% to 8% of income reached an astonishing 26% in the second quarter. Preliminary data for 2020 show total savings for 2020 was $1.6 trillion higher than in 2019. And that was before the $900 billion stimulus.

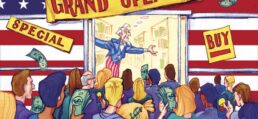

President Biden now wants another $1.9 trillion bill, which would further swell potential purchasing power and impede production by more than doubling the minimum wage and paying more than half of unemployed people more than they make working. Assuming this new spending occurs by September, when the vaccination process should be largely complete and the economy largely open, the Biden plan and the December stimulus would add another $311 billion a month in purchasing power into the fall.

The monetary-stimulus machinery is also beginning to smoke. Since January 2020, Federal Reserve assets have risen 78%; in dollar terms, the Fed has acquired more assets in one year than in the six years after quantitative easing began in 2008. But unlike then, Fed asset purchases are adding to the money supply rather than only being parked as excess reserves in the banking system.

Though economic activity remains depressed in the new shutdown and low monetary velocity is now muting its effect, M2 money supply is still up by 28.3% over the past 12 months. And that’s before the Fed monetizes the next wave of stimulus. For comparison, money-supply growth peaked at 13.8% in the high-inflation era of the 1970s. It may sound old-fashioned in the brave new world of “Modern Monetary Theory,” but is there not the need for some caution here?

Despite recent shutdowns, vigor is evident across the economy. Housing sales are at a 14-year high, private business investment is up 25%, the IHS manufacturing index hit a six-year high, and agricultural prices are at an eight-year high. The Fed projects 4.2% growth in 2021, and the International Monetary Fund raised its U.S. growth estimate to 5.1%. Even the negative December jobs report showed underlying strength. While the leisure-and-hospitality industries lost 498,000 jobs as a result of renewed shutdowns, the rest of the economy added 358,000 jobs.

What about Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s claim that a new stimulus is needed to “help families at risk of going hungry or losing the roof over their heads”? Last year the average household in the bottom quintile of earners received more than $45,000 of government transfer payments from any combination of more than 100 programs and credits, and 22.6 million households received food stamps. The evidence of hunger comes from the advocacy group Feeding America, which defines respondents as “at risk of hunger” if they say they’ve worried about food security on at least one day of the preceding year.

Researchers from Harvard’s School of Public Health have found that concerns about food security expressed in surveys don’t decline when food aid increases. As for losing a roof over their heads—with income and savings up, most people who chose not to pay their rent or mortgage did so because government eliminated the consequences of not paying. In the process it ripped off retirees who own many of the nation’s rental properties and finance countless mortgage loans through their pension funds and insurance policies.

Rising vaccinations may restore consumer demand in leisure and hospitality even before venues are able to ramp up their capacity. Damaged supply chains are causing some of the longest delays in a quarter-century. International shipping challenges are driving up global freight rates.

Policy makers are acting as if running up the national debt and printing money doesn’t matter. Yet all the factors are present to generate rising prices and eventually higher interest rates: excess fiscal stimulus, excessive money-supply growth, impaired domestic production capacity, and impaired international production and transportation capacity. To this volatile mix, Mr. Biden is promising to add regulatory assaults on energy, finance, small businesses, labor and health care.

Perhaps the resulting impairment of economic capacity will prove manageable, but given that such action is occurring at the very moment of excessive fiscal stimulus on top of a tinderbox of monetary expansion, it is putting the nation at risk. Unless members of Congress are willing to spend no matter what the consequence, a new stimulus bill now is probably a risk not worth taking.

Mr. Gramm, a former chairman of the Senate Banking Committee. Mr. Solon is a partner of US Policy Metrics.